"Sidewinder" Only Animate Thing Feared and Dreaded

by the Prospectors of Great Western Desert, Says Pioneer

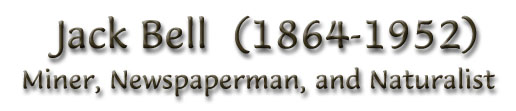

By Jack Bell

The Sidewinder is the only animate thing that is feared and dreaded by us fellows of the great open.

There is but one other reptile that is a notch higher in common hellishness, but one other snake that has the devilish hatred and the insane courageousness

under all circumstances.

His forbears must of a certainty have been the blood relation to the court of the Malay country.

He attacks in the same manner, his movements are even faster, his style of combat is more cunning, and he fights until the death.

Poco Diabalo is a fitting name for him.

So the Indians call him, down there in the great open places on the deserts of the southwest, where water jumps are never less than 50 miles.

Oh, yes, I clean forgot to say that this fearful thing is a desert rattlesnake, he has several names in Latin that mean nothing to us.

What has been said of him by naturalists make us laugh.

He is merely a small rattler to these high brow chaps.

To us he is a lurking and horrible death.

What the writers say of his habitat and his habits is unknown to us, what is really written of him is burlesque to our way of thinking.

These wise sharps don't give this sneaking, living destruction as much space as they do a common garter snake.

Why? That's easy.

They have never studied him in his own environment.

They have never mushed the deserts between these water jumps, they have never cut across one of the 60-mile basins of shifting sand dunes, with a couple of jacks, shy of water.

To short cut to the reason they know absolutely nothing about him except from specimens they have probably seen along well-broken trails of travel.

The side-winder lives in the red barrens of the deserts of the southwest.

I have never seen them in the upper reaches of the Mexican country.

THis snake never attains a length greater than 18 inches and his girl is never in excess of the size of one's small finger.

He is of the mottled variety similar to the common water snake of the eastern sntates.

Of rattles he is generally equipped with but three or four and of course the button.

Never in all the 30 some years have I heard of a single case where this reptile gave warning.

Not even when he is fighting will he make any effort to wiggle his tail as does every other one of the rattlesnake family.

But he will switch his tail like an angry cat when he starts a fight.

This is the one crawling thing that has the one peculiarity that is possessed of no other of the snake family.

When he is within a man's radius he will go like a brown streak toward him, not away from him as every other snake does.

There is one single exception, the cobra.

He rarely ever coils as do all the venemous species.

He makes two great curves with a third of his length and strikes with deadly accuracy.

He strikes from every known angle while crawling and he fairly streaks through the sand and small growth of cats claw like the swift.

This little instrument of death will be going away from one human mark toward another and in doing, will dart his head with mouth half opened at the person immediately behind him.

From this very peculiarity he was given the name that he bears - wide-winder.

He also has another unusual mannerism.

When he strikes an object he bites, that is he will with the force of his one-third length hit an object and when he has reached it invariably makes the same motions and with the same results

as the chewing animals.

Almost instantly after the first strike he will open his jaws and take another bite and so on until it is killed or drops of its own accord and then he will

raise his body for several inches and sway and go through the peculiar shifting that shows his head in every known vantage.

Fear - he has none.

He is a fighter from choice and hunts it at all times.

His enmity is always directed at the human being.

He is never known to strike or lie in wait for anything else, with the exception of the very small lizard family and beetles.

I had the ill luck to be struck by one.

It was this way.

Down there is a species of rattle weed that in some cases will make a sound like the cinnamon rattler, the big fellow that we seldom ever kill.

One gets a bit careless, making trail across a waste like the San Augustine plains going down the long way which is necessary on account of the broken country on the narrow crossway.

I was walking ahead of the jacks, half boot deep in sand that, by the way, is pure silica and white as snow.

One must always carry a long handled shovel or a stiff switch to kill this vermin.

You know a snake is very easy to kill, by striking him sharply across the back anywhere.

But with this accursed side-winder every precaution must be taken on account of the rapidity with which he moves and the every angle from which he can strike.

My attention was called to one of the burros that had a shifted pack.

Now there was a bit of cats claw growing through the sand piles and windrows that always cover and uncover as the winds shift them about.

When I left the lead of the animals there was no snake in sight.

After two hours travel I certainly killed no less than 20.

After I tightened the cinches I walked around the animals to break trail.

At my second step I heard the rattle weed.

Years of desert life automatically directed my attention toward the peculiar noise.

Just at the point a dirty brown streak darted at my shin.

Like the fool I was, having examined many specimens in every posslbe manner.

I watched him as he acted his chewing stunt.

I had heavy laced dry tanned half boots - the ordinary corduroy trousers, heavy woolen socks and heavy flannels.

For perhaps 10 seconds he chewed.

Then dropped to the ground, lashed his tail and spun his head and neck in every direction at once.

He fairly trembled with rage.

Once I imagined I felt a light prick on my shin, but never gave it slight thought right then as I never for a moment thought that it was possible

for the snake to reach the skin.

I had at this time a pair of dried fangs that I had taken from one of his kind on one of the deserts below and I could not figure how this little one

could penetrate so far.

But he did nevertheless.

I killed him pronto.

I made dry camp, stripped my leg and sure enough there was a red dot that had begun to swell.

It was just about what a hypodermic needle would do.

I was feeling a bit sick at the stomach.

Then a pain would shoot through my whole body.

I was scared.I had a long mush ahead to get out of the sane either way.

The nearest ranch was on the 30-mile stretch that was before me.

I was rattled for a minute, as I had witnessed several deaths from this same cause, and then I thought of the hypodermic outfit that I had in my shirt pocket,

a little emergency case with an always loaded syringe of permengate of potash.

I shot the whole thing into where the tiny red puncture was.

Then believe me I was sick for a couple of hours, and while I was under the canvas oe of the burros backtrailed and I had two packs for one animal, and

in travel that made 50 pounds a load.

But I was really sick.

I tied a small rope about my leg under the knee.

But this was after I had dissolved another tablet and shot it into the little puncture.

Of course my leg began to swell, but that was as nothing to the molten hot lead that was in every vein and artery.

I was getting more and more scared all the time, too.

When the sun was straight up I was about all in and that's the truth.

Guess I went kinda out of my head, because I kinda come to myself just as the big red balloon was going down over the hog backs in the west.

My leg was as big around as my body, my eyes did not seem to want to stay where I directed them.

They wanted to turn right back up into my head.

Say pardner, be careful of side-winders if you ever have faith enough to take one of our trips into the big places down there.

Well I got through the night somehow and there was that poor burro without any food, but I had some alkalied water and gave him a sip.

I was getting shy, too.

There I was getting short of water and strength too, and my leg the size of a barrel.

It was a case of root, hog, or die with me.

I guess I was the first one that had taken this "short cut" for a long time, and of course whne I was up against it, there was no show for any Indian or Mexican to show up.

I made up my mind to make a try in the morning.

I couldn't leave my outfit there.

Had to take it along 30 miles to a ranch and anything might happen trying to get across.

I started at gray day.

God bless that little old jack.

I hung on the side of the pack and he seemed to sense in an almost human way that I was up against it.

I dragged that bum prop all the way and landed at the ranch down on the Datil plans at midnight.

John Coxe, who is a history in himself of the past 40 years down there in the Indian country took care of me, and I needed it, too.

The flesh sloughed away from my shin and to this day I have the scars where that hellish varmint struck through my boots.

Now there is another thing that I find obtains, not only with me, but with a goodly number of other desert rats that have been scratched with

the snake and Gila family.

Every year, during the excessive heat, along my shin there appears a great mottled green and reddish brown area showing from where the puncture was given,

then it spreads several inches around it, looking for all the world like a bruise.

In the north reaches of Death Valley there are any number of springs - bitter, arsenical and otherwise.

Many deaths have been caused by these springs, tenderfoot prospectors filling up with the water when their thirst-crazed burros

cannot be induced to wet their muzzles.

There it is again.

Give the burro freedom and even in that little area of Death Valley, which has been so much written about - a joke to the old prospectors, by the way - he will invariably lead to good, sweet water.

Sometimes an old prospector has an accident and loses his water.

He may not know exactly where the next water hole is located.

We will start on the trail and turn the jacks loose.

Down through the canons, across the sands, into the red hills, and through the pure white miles of alkali, they will surely lead their master to sweet water.

It has been done countless times.

Not only that, but they will keep right on and lead out into a grass country somewhere.

A remarkable thing about the burro is that he never fails to remember a country that he has once been over.

He will always take the exact line of his previous march.

A little kindness and a bit of salt or sweets of any kind will never fail to win a burro.

If you feed him at noon he will invariably be back at the same time and at the same spot.

It is hardly necessary to say that all these stories about a burro living on tin cans and rubbish are nonsense of the rankest kind.

What he does fool around is a can for its the sweet taste from the paste used in putting on the wrapper.

This same reason applies to any paper that has salt or sugar sticking to it.

He is inordinately fond of both of those things.

There is but one vegetable he will not eat - cabbage.

He will find good, nutritious forage where any other animal would starve.

There is a certain cats' claw on the dessert that he will actually fatten upon and he will take a chance at cactus if he is forced to it.

Cactus is really fine forage, but hard to masticate on account of the spines.

When a blizzard is brewing, although the weather conditions at the moment may seem perfect, the burro will make for shelter.

If it is in the

Continuation of Article

mountains where there is timber, he will find a well sheltered place on the edge and remain there until after the storm.

On the desert he will at first become restless.

He starts away from camp, then returns, and then starts away again, and almost always he will have his ears plastered down to his neck.

The veteran prospector knows that there is either a severe sandstorm coming or a blizzard with snow dust.

The remarkable vision of these animals is another revelation to anyone who is not familiar iwth them.

A burro will sight an object far beyond the vision of man.

The animal will stand for an hour at a time with his ears pointed in the direction of the object he has seen and the man knows there is some living thing

within the animal's range of vision.

By remaining beside the burro the man will be able to make out the object after a while.

It may be a bear, a horse, cattle, or a human being, but the little burro will see it long before it is visible to his master.

The burro mother rises to the tragic when she is defending her young.

I have seen the mother of a young colt standing on the defensive when near a mountain lion - and the mountain lion, be it known, is might particular

to any kind of colt meat, whether horse or burro.

The jinny will circle round and round her young, roaring out a cry for help with the peculiar call of the burro, which means such a joke to the tenderfoot and

so very much to the prospector.

It will not be long until another burro, or perhaps a couple of jacks will show up.

They will form a ring about the colt and it is not once in a thousand times that a wolf, coyote or lion will take a chance when there are two or more

burros to fight.

The burros' actions are lightning and their aim, with hoofs and teeth, is perfectly accurate, adn the result is death.

Burro motherhood is worthy of a nature book in itself.

The little burro colts arrive mysteriously, and no man, not even the Mexican herder, knows when or where.

On the day the new arrival is expected the burros will assemble for miles in every direction.

The jacks stand on the high places and give forth the call, which is passed along.

It was shown last year that a burro visitor to the birthday will come 25 miles.

Then, about the time the little burro first sees the light of day, there is a bellowing by the big herd that can be heard for miles

and for hours at a time.

This is their manner of expressing joy that a baby has been born and that all is well.

Last summer I went up into the hills at midnight - a moonlight night at that - and began to search for the jinny and her colt.

The big herd shut up instantly.

I prospected all night and the next day had the assistance of three Mexican herders.

It did not avail us, and the hiding place of the jinny up there in the snow spruces was never found.

One of the herders has been in the hills with the flocks for 40 years and said he had never been able to locate the hiding place

of a burro under like conditions.

But the big herd wandered about the vicinity, no doubt as a guard against the possible visit of a mountain lion or any other foe,

because the burros wandered in regular order for all the world like a military guard.

On the third day I found the mother and colt.

And how that whole herd loved the little jackrabbit specimen of an animal!

The burros would walk round and round the colt, sniffing and curious.

The whole big band of burrows followed the mother and the little fellow every minute of the day and night.

There is no other animal that loves the young as does the burro.

And when the little colt begins to kick and bite his elders in play, the delight in burroland reaches its climax.

(Copyright, 1923, by Jack Bell)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen