|

|

|

|

|

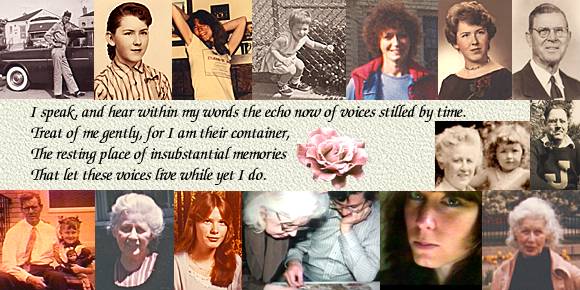

Growing up, there were always five of us - mother, my grandparents, my brother and I.

Father had been left behind by mother when I was six weeks old, and so I never counted

him in that first, essential number that told me who I was by what I was part of. There

were just the five of us.

When I was 9 years old, brother left home and, for the first time, the rock on which I rested moved. And suddenly there were four. Then, one by one, like Agatha Christie's Ten Little Indians, grandfather and grandmother and mother died. When I tried to find my father, I discovered that he, too, was dead. I've built a new family with Paul and a house full of four-footed, furry children. But sometimes when it's quiet, and I'm very tired, my mind jumps back to Sunday mornings when my first family was still together. The sun angles through the room, creating a bright stage upon which dust motes dance above the new, moss-green carpet. Grandfather's pipe smoke fills the living room, interrupted only when his newspaper page turns and temporarily blows away the cloud that halos his grey, beloved head. Brother is on his way out to meet friends, while mother sits in the dining room writing in her diary. Grandmother is in the kitchen making our favorite family dish, a sweet bread pudding. She sings as she works, one of those old music hall songs that make you sweetly cry. An outside noise catches my attention, and suddenly I notice that my eyes are damp. I blink rapidly to clear my vision. It must have been the song. |

|

Like many a habit a child learns from mom,

As facts entered in, other facts entered out

Imagine poor Holmes with his stuffed attic drawers |

|

The hikes that we took, when I was a child, Wound through canyons and prairies and sweet sylvan nooks Filled with wildflower storefronts and auto-clogged creeks. I walked with my mother and saw with her eyes Carrying all of her years with a ten year old's pride. She didn't have money, we'd only have tea, But she stuffed me with cupcakes of sweet memory.

She talked as we walked of her past college days,

And each of these facts and small tales she would tell |

|

One Sunday, a poet's obit took mom back To the days when the grease from his hair stained the back Of the sofa or wall, it isn't too clear. But she spelled out his name and I hear John Rose Gildea from the single small tape I recorded of mother that precious past day When sea gulls flew over the burgers and mall And mother still lived without Valhalla hall.

I always knew mother was smarter than I,

So now the pastel sits inside of a mouse, |

There was always singing in the house when I was a child. Daddy would sing "Camptown Races" and

"Turkey in the straw." Grandmother would sing "Bill Bailey" and cry while she ironed. Daddy

never could understand why nana loved so to sing and cry. I can.

Daddy was the stability and balance in our family. Grandmother was emotion and mother had a bit of the

wildness of a bird, but grandfather was the solid center that let our family function. His family came

from Sherman, Texas and he loved them deeply. Almost every week a letter would arrive addressed to

Dear Brother and signed Sis.

He taught me to garden, though I don't remember anything very significant coming

up. I think I was too impatient to let the garden grow. Luckily, love grows very quickly. And the more

you pick it, the more there is. When we lost Daddy, we lost something irreplaceable. Everything was always

slightly out of kilter without him. Somehow, it seems right. The world shouldn't have been the same

without him in it.

My father was Army, and brother and I were born Army brats. Since Mother left father

when I was 6 1/2 weeks old, I never got the chance to enjoy the distinction. Tiger,

as my father was called, was born in Canon City Colorado in 1905. His mother, Catharine,

came from a wealthy New York family and married first the son of a manufacturer from

Buffalo. At some unknown point, she suddenly ended up married to Jack Bell, my father's

father, and living in Canon City. Together she and grandfather published a local newspaper,

the Canon City Cannon, which "went off" once a week. Grandfather was a mining engineer and

a miner, and had won and lost fortunes from Alaska to South America. Apparently gambling was

in his blood, because he took one too many gambles with grandmother's affections and she

found out. The result was a divorce and grandmother's move to Denver with five year father and his

half sister Catharine, from grandmother's first marriage. Eventually grandmother married

Robert Van Deusen, who raised my father. The Van Deusen ranch must have been a wonderful

place to grow up, but father's stepfather had a heavy hand. At a very young age, father

lied about his age and joined the army.

It was while he was posted as an ROTC instructor at University of Chicago that he met

mother in a scheduling conflict over a typewriter. She

was a student there. Sometime after she graduated college, and while she was visiting

in New York, they were secretly married. That was on August 27th, 1934. That

Christmas Mother finally told her parents she was married. They were shocked, but

believed that a wife's place was with her husband, and sent her off to New York with

an allowance to help her survive on the salary of an Army private.

Father worked mostly as a rifle instructor with ROTC classes, though he was in intelligence

for awhile during World War II. Most of their marriage they lived in the Greenwich

Village area of New York City and later moved to Manasquan, New Jersey, a coast town

where I was conceived. Mother used to describe standing on the beach during the day and

watching U-boats rising and at night watching ships burning. She said you always knew

there were bodies washing up when they closed off the beaches. When my brother would play

in the ocean, they'd have to take him home and wash him down in gasoline to get off the oil

from the downed tankers.

Few letters remain of father's and, up until a year ago,

no poetry or writing remained either. Mother destroyed or mailed back everything she had.

As a journalism student,

mother was able to go to dinner with Robert Frost and Frank Lloyd Wright, and did give them

both a small book of father's poems. I've often wondered if it ended up in a hotel trash can

or was thrown into a library somewhere. But, regardless, no copies of his books have

ever emerged. It took learning how to search for poetry while investigating father's 4th

great grandfather, Major Henry Livingston, Jr., to prove his authorship of Night Before

Christmas, that my husband and I were able to find what poetry

was published in the University of Chicago Daily Maroon. I knew that he had published

there from mother, but I learned that he had actually written a column for the paper called

the Whistler. He used the name, the Blind Tiger, but he wrote under various and sundry

pseudonyms. I cried when my husband's microfilm roll turned up father's column, and I was

shaken when reading it to discover that it was in that column that he courted my 17 year old

mother. And she answered him back!

Mother said that I wouldn't have enjoyed father if I had known him. He was wide open

and emotional, traits she didn't share. While they were married, he would come home from work

and stop off in the building super's apartment for tea with the super's wife who would tell

her about the party going on upstairs. Mother said that if she was tired, she would throw

out the weakest one there and then work her way up until the apartment was empty.

If strong, she'd start with the strongest and empty it out faster.

Father enjoyed literary types. Mother found their conversations self-indulgent. On one

occasion, the discussion turned to prostitutes. It turned out that mother had never met one.

She didn't notice one of the gentlemen leaving but she did notice when he returned with

a young girl, looking very nervous and out of place. Mother served her milk and cookies,

sent her on her way, and reamed out the gentleman for embarrassing the girl.

Mother didn't see her stories as wonderful, but I thought they were that and more. Once,

when father had to leave town, he worried about mother and asked some Italian friends to

keep an eye on her. They did, following her everywhere. Unfortunately, he forgot to tell

her he had done it. Their upstairs neighbor was a stripper. In her apartment were

spotlights so that she could pose. Her mother spent the day sewing hook and eyes on

her daughter's costume saying in her only English, "My Rose is a good girl."

I can't tell if mother was right or wrong about how I'd feel about meeting father. I am

sorry that I never had the chance to make that decision for myself. When I was in high

school, I tried to find him. I never did. Later I learned that he had died soon after

my ninth birthday. In one of his letters to mother, father said that he didn't know anything

about little girls, but if I was anything like my mother, he trusted me to help him learn.

I'm so sorry I never had the chance to do so.

I graduated in the top 2 of my grammar school class for grades and was tops for absenteeism.

Whenever I wanted to stay home, grandmother would support me. I would sneak out early

in the morning to stand barefoot in the snow until I would start to shiver, then hurry in

to sit in front of the hot air vent until I began to sweat. It was usually good enough

to get grandmother to support my staying home.

Sick days were wonderful days. Nana would enscounce me on the sofa so that I could be part

of the family life and bring me Seven-up, potato chips and vanilla ice cream. I'm sure

there were theories about why these three things would make me well, but I probably didn't

ask too many questions.

Grandmother was very grateful to live in the modern days of TV dinners. When she died, we

found the bottom drawer of the refrigerator filled with empty TV dinner pans. That I could

understand, being a packrat, because they might come in handy someday. What I never

understood was why we found all the lids as well.

The family was

very grateful that she loved TV dinners. Grandmother was a really bad cook. I remember a cake

she cooked from scratch that she lifted from the pan and bent back and forth. If it had been round,

it would have bounced. The one good receipe she had was for bread pudding. I never thought to ask her for that receipe

because she was always the one who made it. One of her sisters wrote it down for me at grandmother's

funeral. I am so very grateful.

Grandmother was a fighter. She believed that you dug in and did whatever it was

necessary to do. Excuses could make you more virtuous while you did whatever it was,

but excuses weren't what you used to avoid it. I never doubted for an instant that

she loved me with all that strength and all that energy. I loved her, too.

There were stories of boarding schools and some quieter stories of her being thrown out

of more than one. I wasn't the only one to think Nana was beautiful. Anyone who knew her when she was younger always

talked of her beauty. On grandmother's way to work in St. Louis, she passed a firehouse. Nana

loved to tell how the firemen would line up at the time she was due to pass and just stand there,

politely, as she walked by. I loved that story.

Nana had been a practical nurse and she was always the one they called when someone hurt themselves

or there was an illness on the block. She was the one who organized people to collect

money for children when the Polio epidemic hit. She was the one to call City Hall when

there was a neighborhood problem. Grandmother wouldn't have known how to step back from

someone who needed help.

If I am, indeed, made up of qualities from all of my family, I am very glad that nana was there

to add to the mix.

"That's the good witch," she explained as we descended from a bus

in the foreign country on the North side of Chicago, we being

from the South. Seeing me begin to cry from fear of this

nonsequitor, she began, the one and only time, to take me through

the logic that led to this result. It was simple, really. In

the North side of a city, a woman dressed in blue resembling an

illustration and wearing such a gentle smile had brought to mind

the book of Oz and the good witch who ruled the quadrant there.

She tried to explain that she had found the comparison funny and

so had thought to share with me. But, then, mother found much of

life to be amusing.

Knowing that there was a logic there made all the difference from

then on. I could take her statements and put them in a

perspective that let them be ignored. And when I, an adult, was

stopped for some such misunderstood remark, it was easy to

believe that the source of the confusion was in my own obtuseness

and not the faulty logic of inattentive friends.

It is still my besetting sin when writing, though so many other

errors correct themselves naturally now as I watch their patterns

reemerge. It's only in this difficulty of recognizing when the

right amount of words have been laid down to lead to that result

that I hear again the distant echo of my mother's voice. "That's

the good witch."

Mother became a bureaucrat, a social worker with a book that she

brought home to fill with different pages every night as long ago

I once filed tax code for the state of Illinois. She knew that

book and every detail it contained. She was the source to whom

all went for information on whether this one could get food

stamps or that one extra meals. At least this exercise made use

of that great memory far better than the license plates she

memorized for fun when we'd go walking in the park, or dollar

bills whose serial numbers stayed with her long after limp bodies

found rest in cash register drawers and poor boxes and

hands of children waiting for a bus.

I took that mind for granted until the day I sat beside her

waiting for her body to give up its final strength. She asked me

how could everything that she knew just disappear. I had no

answer then and I still have none today. I wish I knew.

Education was central in our family. The year before mother died at 72, I was

finally able to convince her to drop her master's course load from two classes

down to one. I know she was disappointed not to be able to complete the master's

program within her lifetime. Whenever we would travel, mother would carry her

course books with her. She was fragile in the last years of her life and would tire easily.

We would walk from bench to bench. It was a leisurely way to walk through life.

As soon as she would settle down, out would come the accounting book or the statistics

book. For her last birthday, we traveled through Washington to Williamsberg, Virginia.

I wanted to get her a gift that she would love and I found the perfect one -- a large

selection of pamphlets from the International Monetary Fund. If you could have seen her eyes!

Jeanne Van Deusen - fresh from Germany

Jeanne came back from living in Germany with an interest in wines and joined my husband

and I on the obligatory Napa tour. Since I'm a wine-collecting tea-totaler, she and Paul

both appreciated having me along on winery tours since they got to divide up my samples

between the two of them. She came back from Germany with wonderful photo books of

places I've only read about. It's so great that she and her sisters have had an opportunity

to travel, to experience so much, and to learn a new language. It makes a wonderful

set of memories to look back on through her life.

Jeanne Van Deusen - at 2 1/2

We were very lucky to be able to have Jeanne come for extended visits with our family on

a number of occasions. This was the first. She learned to drink through a straw while

we sat on stools at Walgreen's drug store. Then she learned to blow bubbles.

Jeanne Van Deusen - an adult

Jeanne lived with us for one year of high school and for several years after college.

It was such a joy to have her with us. I found such beauty in her eyes and such sweetness

in her soul. She always talked of wanting to have a child. She has three of them now and I

think they must be very lucky.

Jacqueline Lae

Jackie was married to my brother for almost 20 years, and I still think of her as my sister.

It was Jackie who took a 13 year old bratty sister-in-law and taught me how to dance.

You can't leave someone in your past

who's taught you that. Jackie's now a registered nurse, volunteering occasionally for

busman's holidays in third world countries. She has a large heart, and an adventurous soul.

I usually see her on her way to exotic places I just read about.

Mary Van Deusen - graduating high school

I attended Aquinas Dominican High School on Chicago's south side. My dreams of being

a librarian changed gradually into a dream of being a classical Astronomer. I won awards

in science fairs every year, which just reinforced the idea. And falling in love

with my optics instructor at the Adler Planetarium didn't hurt it much either. Fondest

memory: lying on the floor of the main chamber listening to medieval

music box music while watching the stars being set by for the Star of Bethlehem show.

James Homer Butridge

Grandfather was a consulting field signal engineer for railroads and subways. He traveled

the world doing this and would bring back exotic dolls and toys on his return. He invented

the flashing yellow signal for the railroad

He

was a man of great dignity, intelligence and love. There was always a reason for him

to take a grocery bag from me as we would walk home from the store - it balanced his other

bag and made it easier to walk. We spent hours in his 1952 dark

blue Packard talking while we waited for mother to get off the bus so that we could

drive her the block and a half home. We were more than grandfather and granddaughter - we

were deep friends.

James Homer Butridge - Daddy

Because I never knew my father, grandfather became Daddy. We were bound together with

the deepest ties. Every Sunday, when I was small, I would curl up in his lap and have him

read the funnies to me. For hours, he would listen to my multiplication tables and spelling

assignments. Irrational as it may be, I still emotionally believe that he loved to listen to all those numbers.

Bradley TenEyck (Bell) Van Deusen

The Boy and the Man

![]() Bios

Bios

![]() Poems

Poems

![]() Letters

Letters

Jennie Butridge - Nana

I remember sitting on the front porch while nana showed me toys to make by tearing up

newspapers. While she did this, she would talk to me about the values that a child and

an adult must have. This is where I learned that "two wrongs don't make a right" and

"you get more flies with honey than with vinegar." She walked me to school until the

school asked her to let me walk alone. And I'm sure she missed me very much. I came

home for soup and sandwich every day until finally it was decided I was big enough to

eat lunch at school. I know that separation was hard on nana. If she could have kept

me home from school and with her every moment, she would have done it with joy.

Jennie Audrey Dribben Butridge

Grandmother was a rough and ready soul. The stories are confused, but what I learned

from mother was that grandmother had been an illegitimate child of a well to do family

that had gone West with the Roosevelts. She had been born in Butte, Montana on a ranch. I

remember stories about her pony and cart and an Indian she would drive out to visit.

Her friends were the cowhands and her language, as a result, somewhat salty. I didn't

know this until I became an adult because she completely moderated her language while

I was growing up.

Jean Audrey Butridge Van Deusen

The mother of my childhood was laughter and anger and

brilliance of a tragic waste. She was serpentine in logic and

frightened me, a child, by momentary surfacing of thoughts as

unexplained as passing views of Nessie's humps above a Scottish Loch.

Jean Van Deusen

There was never a man in my life that mother completely approved of until Paul.

She adored Paul and he adored her. This statement is so simple in the

saying but so significant in our family -- on occasion, when Paul and I would

argue, mother would take Paul's side. I'm still flummoxed at the concept, her

attachment to me was so overwhelming and her prejudice against anyone who

could possibly hurt me so intense. But mother found a very deep trust in

Paul's love for me and so she could afford to love him back with that special

love she reserved for her children.

Jocelyn Lee Mary Van Deusen

Jo was a fairy princess of a baby. I never knew they came that beautiful. She is my

brother's second child and first daughter. She has lived in Germany so long that she now

speaks English with the most delicate of accents. Her children are as beautiful as she was,

and is. Watching her with them gives one faith in the continuity of nature.

![]()

![]()

![]()

[Family,

Genealogy,

Friends,

Pets,

Television,

Computers,

Writing,

Links,

Roses,

Wreaths,

Stained Glass,

Birds,

Home,

Favorites,

Site Map]

![]() Copyright © 1996, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 1996, Mary S. Van Deusen