DO YOU KNOW -

That the magpie, the confidence worker of the feathered world, has not one friend among his fellows?

That this jokesmith and murderer of the hills has the cunning of the fox and can imitate every bird known with such sureness that the birds themselves are hoaxed?

That the water ousel is the most companionable, engagable, living thing that haunts the rivers of Nevada?

That he has no enemy on earth that he really fears and that he renders great service to mankind by eating the eggs of insect pests?

That the kingfisher will return, year after year, to the same feeding grounds and often acquire names by persons who watch for them?

That kingfishers in Reno have been named by their observers "Riverside," "George Wingfield?"

That the fish-hawk, the hold-up man of the streams, never touches the smaller fish, but confines himself to the larger species?

That he kills his prey by powerful blows with his heavy beak?

That the mother quail, in order to protect her young, will simulate a badly wounded wing, flutter about in distress, and gradually draw a human far away from her nest?

That the raccoon is one of the most cunning of animals and makes one of the most lovable of all pets?

That in the camps in the hills they often become so tame that they actually become a pest, and will even romp about with a dog just like a pair of puppies?

|

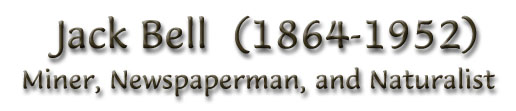

Jack Bell's Interesting Tale of Wild Life of This Section of Nevada

Beautiful Birds and Interesting Animals Live Near Reno, and Can Easily Be Seen by Lovers of Nature, Nevada's Naturalist, Jack Bell, Says in his Article

PART II

By JACK BELL

(Copyright, by Jack Bell)

Have you ever sat in the quiet, the stillness of the great open places far, far from the fenced in, modern advances of civilization?

Have you ever turned out before the steel grays appear, that fraction of time between the dense darkness of the night and the sudden opening up of the world?

Have you ever seen the awakening of a new day from its restful sleep, in an atmosphere charged with stimulant-like old wine, into the perfume of the spruces?

Have you ever experienced that infinitesimal, sudden change from black destiny to pure light?

And heard the cheep, cheep of the birds, the beginning, the heralds of a new day?

Then the burst of song joined in by the carols of the white crown sparrow, then on and on comes from every tree, bush and rock the grand opening chorus of the whole feathered legion.

The sweet tones of the warblers vie with the songsters in their worship to the Creator of all things.

Now the screech of the eagle and the hawk, the discordant scolding noises of the camp robber and crested jay, and the piercing, sharp, peculiar whistle of the ground hog that makes

his home in the great slide rock grounds.

The porcupine comes along with his movement so slow and dignified, the bobcat mews as it sits on a high ledge and plays with the young, as does the domestic species.

A deer raises his antlered head and sniffs to the four directions.

In the waters the mink and the raccoon start their search for their breakfast.

Then as suddenly as the music began, a matter of five minutes, all ceases and again there is a stillness of the eternal hills and the feathered tribes and the fur bearers begin their day.

All Near Reno

With but little variation all of these interesting, never-to-be-forgotten details and absorbing pleasures can be found near Reno.

The magpie is a joker, robber, comedian, jokesmith, destroyer of the eggs and young of the smaller feathered denizens of the open.

He is a confidence worker, he has no friends - every single living thing of the small bird and animal life is his deadly enemy.

Invariably they go in pairs, sometimes flocks, depending on the locality and the food that can be found.

They will feed on a dead carcass and will not eschew a small snake, birds' eggs, the young of all the birds.

They have the cunning of a fox.

Their imitations of every single bird are wonderful - so absolutely perfect that they cannot be separated from the original,

and the only method to determine the difference is to locate and observe Devil Magpie when he hides in a curtain of leaves in a tree

or in the impenetrable denseness of low growth, where it is impossible to see him or to break through.

However, he will feed upon sweets and anything he can peck and tear, when in captivity.

He is a rascal of the steenth degree.

Real Confidence Mano

Interesting? Of course.

He may be likened to the suave, handsome surface-bred confidence man and stock selling crook that lives by his wits and upon the weakness and gullibility of the general public.

So the magpie conducts his affairs for food and comfort.

His plumage is also comparable to the human type, he wears a dress suit, evening clothes of a gentleman, black and white, and like his human comparison, delights in the finesse of

procurement that causes suffering, shows no mercy and no compassion, and glories in degenerate achievement for his own ends.

However, members of the blackbird family, after being lured away in their own bird language by Devil Magpie, sometimes return suddenly and find the magpie hopping and flying about the tules

among the nests, sucking the eggs or devouring the [xx].

Blackbirds Battle

The blackbirds, with cries of assembly, will gather in bunches and one at a time will attack the magpie while the others fly about and fend off the danger from the single blackbird that whales

away with bill and clothes, making the feathers fly in small downy bunches of black and white.

When the attacked jackal tries to protect himself from the one bird, another seeks an opening and all the time the magpie is endeavoring to make a retreat from the massed and crying outraged tule dwellers.

Down on the ground goes the beaten black and white despoiler of feathered and down life.

He crawls and dives through the thick mass of tules and grasses and always hovering over him are the screaming, fluttering birds.

Pretty soon Devil Magpie makes a break for the open ground, flies low.

He is beaten down, again and again.

Now he hits back with tail outspread for balance and begins the real fight for his life.

Several of the rushing battlers feel the wounds of the powerful bill and still the feathers fly from the body of old man magpie.

Now he essays a flight to a nearby cottonwood tree - all that remains of his beautiful, glossy coverage are the long pinions on wing and tail and he looks for all the world

like the figures described in the fight of the parrot and the monkey.

It seems that no other of the breed comes to the rescue of the sorry looking magpie.

He hides away and remains in seclusion until his decent covering grows again.

Live in Trees

His home is in the trees, that are difficult of approach, on account of the heavy underbrush.

He is of the several jay species: Careful observation and the patience of the angler will reveal that Devil Magpie will sit himself half hidden in

brush and tree and amuse himself by mimicking,

and in perfect accord in tone and timbre, each and every note with the same perfection as the song sparrow, for example.

When he has called in the mate of the singer he imitates, then he will squawk out his raucous cry,

take wing to some other place of vantage and listen for a song bird of other habits and who has a distinctly different scale of trills.

He seems to enjoy the surprise and discomfiture of the little fellows he draws to him by his ventriloquy, and he keeps at his devilishness for hours at a time.

It is generally after a feast of some kind that he begins this crusade of jokes and "come-on."

It is common for him to make the noise and scream of alarm of an enemy of the hawk when the latter has captured a field mouse or small reptile and is engaged in tearing it apart and making a feast.

It is his plan to frighten the hawk away and then flop down from some place of concealment and run away with the fresh kill of the other bird, to devour the delicacy, in a place of hiding.

When the hawk circles again and can discover no enemy in sight he flies down to the ground for his meal, then it apparently comes to him that Mister Magpie has been

up to his old tricks, and he soars away to other hunting grounds.

Annoy Burros

One of the troubles that the old-time prospector has with a pack-sore burro is the care that must be exercised in protecting the little bearer of the desert from the

injuries that the magpie inflicts by pecking in the raw flesh.

Many are the expedients used to save the burro from permanent injury from these flesh eaters.

Time without number, and a circumstance as well known as the water holes of the desert, is the punishment meted out to the magpie for this trait.

The old-timer will make a loop of cord about the raw patch, on back or shoulder, stake the animal near a cover where the man will hide.

He does not have long to remain in hiding.

The magpie will alight and before he can sink his bill into raw flesh of the animal the string is given a jerk and the magpie is caught within the loop by both feet.

Reproduce Human Voice

The most startling attribute of the magpie is the ability to reproduce the human voice with absolute expression of the one who teaches him to talk,

many sentences and exclamations, ordinary and extraordinary.

Some years ago an old-timer opened a little cigar and news stand on Eighteenth street in Denver.

He had enough of the big open, so he always argued.

(He is still in the hills.)

He had settled down and was through with prospecting.

For some years he had packed a magpie about with him, and for his entertainment and pleasure, during days of rest and inclement weather,

he taught this bird many long sentences that could not be told from the man's voice and when the prospector began talking in one end of the little shop

and the magpie in the other, the talking was so identical in voice expression that the hearer almost believed that the man was appearing in both places at one and the same time.

Many a stranger has been a bit flustered and disturbed when upon opening the door of the shop, a strident,

heavy masculine voice from the ceiling would break the silence and shout:

"Well, what can I do for you today?

Get busy!

What do you want?"

In consternation the customer would look all over the little store - not a soul in sight.

Just then the rear door of the shop where he had his living quarters would be opened by the owner, and at the same time the magpie would flop down upon his shoulder and begin to talk,

and it was certainly interesting to listen to the double conversation, each in the same voice and using different wordings and exclamations.

Took Long Teaching

"It took me a few years to teach him how to talk.

I had seen numbers of old-timers that put in their winters, when they were snowed in, take the time and patience to teach the magpie to talk,

and they always use the same voice and tones as the person who has worked and patiently developed this human voiced feathered freak.

There is none of the nasty, metallic, grating, disagreeable cackle about the magpie that is found in the talking parrot.

The cussing sentences, of course, are the very first thing acquired by both birds who are separated from their environment by thousands of miles and in such

different surroundings.

Years and years of association with the birds and animals in their natural environment in the vastness of the big, unexplored, unsurveyed open conflicts in many ways with the habits gained second-hand

in surroundings in and among civilization, and the native element where they belong.

The Water Ousel

The most lovable, pretty and interesting feathered chap among them all is the water ousel that makes his home on the Truckee river.

He is rated with the plover company.

This shore bird is about the size of a quail.

They are found in the shallows along the shores.

They are satiny, brownish lead gray in color, with a closely bobbed fan-shaped tail, the dark legs being somewhat shorter than the others of the plover group.

To the observing seasoned angler he is the most companionable, engaging living thing that haunts the river.

He darts here and there will turn his head sideways and study the spects of living food, so small that the human eye cannot determine.

Then his little head will hammer and strike around the rocks for all the world like a woodpecker pounding away on a dead stump.

His feed consists of the jelly masses that harbor the eggs of water insects, that when hatched in turn become the flies of the different species, that develop during

the warm months and can be seen in dense clouds at eventide.

Now something attracts his attention as it moves in the low water along the edges of the stream.

With a cute little run, for he is a walking bird, his head will dart out like a flash and then again and again in the same spot.

Then backward and forward he will stretch and walk, all the time keeping one eye on the water.

Delight to Fisherman

To the fisherman he is a delight.

The angler will stand in the water where it swirls about his ankles.

The ousel will approach without fear and intently investigate every inch of the shallows.

Then when he reaches the fisherman he will likely as not hop on the wading shoe, turn his little head sideways and look right up into the face of the person

who stoops over to get a better view of the proceeding.

Then his attention is diverted from the minute investigation of the human being and he wades out into the water and, with head submerged, will feed and feed until every last particle

of the food is cleaned from the rocks.

He will walk with his head under the water for some time, and in and out his head appears.

There seems to be no enemy that he fears.

Again he will locate some special object in water a foot deep.

Under he goes, entirely covered with the waters.

He stands on his feet and will remain under for a minute at a time and his fast working bill will cover a diameter of a rock like a cooper goes around a barrel.

Then when he comes to the surface he will dart shorewards and perch upon a dry rock, and prune and dress his feathers.

He is the busiest living thing of life along a stream.

The Crested Heron

In stately, solitary grandeur along the edges of slow moving pools, before sunrise, and at the closing of the day, in the perfect concord of ideal outdoor life and surroundings,

will be seen the crested heron.

Particularly at twilight, as the sun disappears behind the bulwark of rugged mountain outline, he will be joined nearby, from out the air, by a descending blue crane, that in shadows

and appearance looks for all the world like a diminutive airplane, with his great spread of silvered wings.

Both of these timid great wading birds get busy as soon as they have made their statue-still stand, with but one long leg gathered and folded up under the body.

Occasionally the heron will emit his unpleasant scream when the crane comes within his bailiwick.

Knee-deep in the waters they stand waiting for the unwary crab or minnow that comes within their zone of reach.

The evening wanes, the bats appear in numbers, the whistling of the wings of the night-hawks is heard above the blur of falling shadows,

and the cloud of insects of the night begin to go by in collected hordes.

Chug! goes the bill of the water fowl into the water.

A wiggling water lobster appears and, with a scissor snapping motion, the big bird stretches his long neck vertical and the morsel vanishes.

The matin sparrow, from the sheltered gloom, trills forth in his wonderful harmony, the big sentinels as they stand, feeding and feeding upon the unwary,

soon begin to grow dim.

Their outlines are almost indiscernible; they fade away; nothing is heard but the music of the running water, wafted, low and lower, as the warm, gentle winds

change to evening's coolness, pulsates the ether, making tones comparable to the playing of a master upon a colossal organ in the vast interior of a cathedral far away.

The curtain of night calls, the displacement of atmosphere can be detected as the heron and crane take wing for their abiding places.

The Kingfisher

The kingfisher is the popular and most familiar of the water feeders.

Many have acquired local names, such as the Riverside, George Wingfield, or Park and Red Budge.

Year after year they return to perch on the same places of observation and vantage.

They will be seen on guy, bridge and electric wires cossing the river.

Attention to them is attracted by their clattering, shrill cries as they leave their regular and unchangeable places of observation.

They sit in this one place high above the shore, for sometimes an hour at a time watching for the crawfish, small minnows that school

in places of safety from the larger enemies and the big trout and mink.

His beautiful crest will ruff up to vertical and like a plummet he will drop, head down, like a diver

and, with a splash that can be heard far above the rushing river, secure his booty to be devoured, as he flies away into the willows near his domicile.

The deadly accuracy of the kingfisher in striking his prey is most interesting and almost any day he can be viewed during his periods of feeding.

He rarely misses.

When he does make an error it generally is caused by some influence that distracts his attack and causes fright.

Very often he will just about strike the water in his wonderful, human-like dive, when something frightens him and he will, with almost unbelieveable swiftness,

change direction, barely touching the water, fly over the stream with his cry of alarm and make for his sanctuary in the tangle of vines and willows.

They will breed in the same place year after year, and rear their four youngsters without molestation, as their nests are so well guarded from destructive agencies.

The Fish Hawk

The big fish hawk is a native of the Truckee and its tributaries.

His method of securing his food is of the order of a hold-up man.

He takes no chances of losing.

Invariably he will seek a rock that has natural advantages for his scheme of taking his victims.

The rock that he selects is near the shore, and where the waters swirl into a little low eddy.

But a few inches deep, with moss and hatching ground for the small varieties of soft fish and insect life breed.

He will stand solitary and alone for long periods of time.

The small fish go about their daily hunt for food.

He never molests them.

His gave are the larger species, the white fish and occasional trout and sometimes a sucker.

His feathering looks for all the world like the boulder upon which he squats.

A pound white fish grubs slowly along the shore.

In a flash the hawk, withoutspread talons and open, cruel looking bill, feathers ruffled, drops down upon the unsuspecting fish.

With a cry of his kill the hawk returns to his hunting post, strikes and strikes the flopping fish until life is extinct, and then takes wing and goes to his unlovely nest far back and high

up in a dead spruce where the food is torn and rended and distributed to the unsavory, rather disgusting looking, scrawny necked young.

The Meadowlark

Shortcutting across the vast carpet of the emerald green, flowering alfalfa, which has a delicate perfume that is so satisfyingly delicious; into the long,

undulating sweeps, as it spreads like a rippling sea in pastoral beauty, down to the river banks, one is transported into realms of gratification.

Quite often a fine specimen of meadowlark whirrs away from almost under one's feet, with a mother's alarm cry that is so pensively sweet.

She will flutter about and cry shrilly for her mate.

Parting the grasses, uncovers the nest.

The little fledglings snuggle down, in downy mass, in terror, with their bright eyes sparkling in fright.

The bird lover passes on hastily, so as not to frighten the little one from their home out into the grasses where some enemy may lurk.

After passing, the mother returns to the nest, departs and, from a nearby rock or fence, will almost split her throat with plaintive sweet melody.

The plumage is yellowish brown and the circle of black upon the breast makes a lovely picture with the sun gleaming on it.

Magpies, Raccoon, Mink, Quail, Kingfisher

and Others Who Inhabit the Kingdom of the Wild

are Presented to Readers of the Journal

for their Pleasure

The Quail

Following the ditch laterals along a fence, there suddenly appears, seemingly from nowhere, a mother quail, running along in front of the person

but a few feet away.

She flutters like a badly wounded, broken-winged bird; she makes a little cry that certainly must appeal to the protective sense of any human.

Then as one gains near her, perhaps with the intent of picking the bird up - she will keep a perfectly safe distance away, a matter of two yards or so.

Then she will lie quietly on her side with the wing in a position of usefulness.

Starting towards her, she will again flutter sidewise, and keep on and on with this camouflage until the human being is some distance away from her nest and young.

This is the method employed by the quail, pheasant and ptarmigan family to lead an enemy away from her nest and young.

When all danger is past she will take wing with a swiftness almost unbelievable and fly directly away, and in the opposite direction of, the nesting place.

Coming upon the nest, the mother and the young, in their hidden retreat, immediately creates a stampede - the mother starts her crippled [xx],

the cunning little brown chicks, exact images of the mature bird, will, within the winking of an eye, scramble from the nest and disappear much

more swiftly than the telling.

It's almost incredible, the absolute disappearance of the little covey of cute brown youngsters.

They are hidden immediately.

Under a few blades of dry grass, a small brown leaf, a bit of dead limb, alongside a small strip of bark, their color making it almost impossible to see them.

They scatter in a circle, no two in the same place of hiding, and within a circle of a very few feet.

The observer must exercise every care that they are not trampled upon.

After having reached a distance of 50 yards, if the watcher hides for a few minutes,

the mother call of the quail can be heard calling the little brood back to their home.

They appear again as if by magic, and back they go again to their nest.

The mother takes her young along the feeding grounds in exactly the same manner that a hen will take her chicks, teaching them

proper food to look for and the methods for safety from the many enemies of the open.

It is true that there are but few sportsmen that think of anything but the sport of killing this aristocrat of the fields and valleys.

They are the most edible of the quail species, with, maybe, the single exception of the ptarmigan of the snow lines and timber line in the high places.

The Raccoon and Mink

A short walk up the river, in the magic of the desert-mountain twilight, the searcher for nature study comes to the canons that break in rugged

masses of rock strewn moraines, boulders from the size of a baseball, then graduated up into the thousands of tons.

The interlacing of dense growth of vines, rose bushes, willows and grasses of the dank varieties, the criss-cross of dead timbers, the decaying treetops,

in all making an entanglement almost impossible to penetrate, without brush knife or axe.

Growing up through this tangled jungle, the groves and spots of slender, quaking aspen, the leaves of which twinkle and flutter and shine in the sunlight.

Struggling down through the lesser difficulties, through the heavy growth and other obstacles, a fairly comfortable place for observation can be had

of the opposite shores of the stream.

This self-imposed hardship is repaid a thousandfold, in pleasure infinite, and in information first-hand, of the natural, almost human, habits and traits,

in their natural environments, of the raccoon and the mink.

There is no pet on earth as cunning, as lovable, as the coon.

Both Very Timid

Both of these bearers of valuable fur are very timid.

They are absolutely different from public park specimens.

He seems to be of another breed when found playing and feeding about in his own natural environment and surroundings of safety.

In any of the canons described, both the coon and the mink can be seen almost any early morning or late evening.

However, evening, with the departure of fishermen and the stir of ranch life along the stream gone for the day, these animals emerge from their habitat

and begin their search for food.

As has been mentioned, the coon is easily domesticated, the mink will always remain wild of the wild, like the bobcat.

They can never be trained or subdued from their wild state into safe and lovable pets.

The raccoon is differently constituted.

He is like the beaver kitten, and as a matter of fact, they become a nuisance, in camp, prowling into every hole and corner of cabin or tent,

and very often cluttering up foodstuffs that mean a long, hard trip to the outside.

The coon will soon learn to become a play-fellow of the airedale, and they romp and tumble about,

just like a pair of puppies.

In the wilds one may take his pet down to the stream and there he will see the cunning habits and deliberate actions of the coon while he is searching for food.

Beware of the Dark

Contemplating a trip up river, one should pay strict attention to the caution of the seasoned angler, who tells the prospective observer to be sure and be out

in the open country before darkness settles in the canons.

If one is caught along the river wilds after dark it means hours of hardships,

danger of injury before firm ground can be reached.

The canon walls are hundreds of feet high and mighty near perpendicular.

It's with a harrowing, indescribable sense of loneliness and acute nervousness that one is caught in these canons with the coming of

the sudden darkness and really a hazard that should not be attempted.

Out from his home in the rocky retreat among the piles and piles of tumbled rocks, the sharp snoot of the animal is first seen before his screened body

slowly emerges from out the tangle between great rocks.

With motions slow, and every faculty alert for a sudden retreat, he investigates in every direction.

When satisfied that all is safe he will then come out in full view and start his exploration for the evening meal.

He is very deliberate in his movements.

Then into the water he wades until his body is half submerged.

All the time he is looking about in every direction.

His baby-like hands are busy all the time feeling about under the water, endeavoring to locate a water lobster or mussel.

At first he brings up a crawfish.

Still turning his head this way and that, and not seeming to pay the least attention to the morsel he has caught

but, all the time, the little fingers and thumbs are busily engaged in breaking away the shell, taking out the white meat.

He will then return to shore with hands still busy with their work.

He will stand, watching and watching, never once looking at the food.

Then when he is ready to eat the small portions, he carefully washes each piece in the water, looks it over carefully before putting it in his mouth.

Each and every little piece of flesh is dipped in the water time and time again in the same manner until the whole has been eaten.

Then he will, with his hands, wash his face as neatly and carefully as a human being, shake his head a few times and proceed with his hunting.

He never fails in the sanitary observance of his food.

When he has had his fill, just like a healthy child, he will stretch and yawn, always vigilant, always watchful, always most interesting.

Back to his home he goes.

He will do his feeding at night, in localities where there is human disturbance during the day and in the evenings.

The coon will live in hollow trees.

He will make his abode in rock piles.

He will [xx] a muskrat's home.

He will dive and swim in the water.

Always along running streams he is found, rarely about ponds or lakes.

Mink is Interesting

In this same environment lives the mink, another interesting family that lives along the Truckee.

The pity of it all is that there is no law in this state for the protection of these fur-bearing animals.

They are wantonly trapped and killed the year round.

They are trapped when their fur is worthless - unprime, and almost unsalable.

It is malicious destruction, and if it is permitted to go along much longer it means annihilation for them and their passing with the buffalo, beaver,

and other animals of the wilds.

The mink does not demand the same tangled retreat and hiding places as does the coon.

A couple of miles up river, in the early morning when the shadows of night begin to leave the earth, long before sun-up, is the best time of day to be on hand to

watch this graceful animal, of almost the same motions and speed in the water as the seal.

In many places along the stream loose running ground goes straight up from the banks.

At the bottom, at the water's edge, the great rocks are ranked.

The immense heavier boulders being at bottom, and tapering upwards a couple of hundred feet, the moraines become smaller and lighter.

All the ground being intermixed with sand.

It is among these great rocks, grow dwarfed willows, cottonwoods and crannies filled with grasses.

There are many places of ingress and a regular catacombs, an impossible place to attempt any excavation to discover the den of the mink.

Just about a half hour's walk up the river brings one to the first abiding place of the mink.

Before the burst of the sun over the Sierras, a beautiful soap bubble colored haze appears in the east, then gradually

the fire sage beams shatter the pale blue of the western sky, striking the mountain tops, as of a dying camp fire.

From the faint candle light, on through radium color, the rainbow coloring comes slowly, for a very short duration of time, in the timbered hills,

the saddles and the draws and, with suddenness over the whole earth, with a glory of a new-born perfect Nevada day.

Mother Mink Appears

From a bunch of feathered willows close along the opposite shore, mother mink came out from the dark shadows of the rock piles.

With her peculiar little leaps she came to the shore of the swift running water and dove, dove with the sliding gracefull motion of a seal and, with its swiftness and

perfect silence, into the waters.

In a fraction of a second she appeared again, with a large crawfish in her mouth, the claws, feelers and tail moving impotently.

Back and forth to her home she would go, sometimes with two of the crawfish in her mouth.

For a dozen times she hurried back and forth with her day's rations.

Then as she came from out of the water, four little babies hopped and jumped streamward to meet her.

She held her slim neck high, to be out of reach of the snake-like motions of her little ones.

Each time she endeavored to leap aside and head for her den she was barricaded by

the elongated, slim streaks of reddish fur and their stubby heads.

She Speaks Firmly

Then the grown-up seemed to say something to them all.

They remained quiet, each small, stubby nose in a semi-circle about six inches away from the wiggling crawfish, held so safely and securely by their parent.

Then she seemed to instantly kill the water lobsters, lay them down in front of her and give to each their portion, after which she nosed each one about face and

headed them all for their home in the rocks.

Back she came after another load of food - but the wind must have changed a bit, for just as she was about to slide into the stream, her uncanny sense of smell

must have detected the presence of he human being, and she back trailed and, never looking to the right or left, hurrifed back into her home in the rock-strewn hillside.

That was the last appearance.

Watching these animals is a relaxation that is of the most healthy sort.

It gives the observer something to think about, apart from the duties, struggles, irritations, and creates a clear and healthy mind to begin a day's work.

The day is brighter for the experience, it broadens one, and during the vigil one is absolutely forgetful of all, else restful and alluring.

The naturalist, geologist, mineralogist, archaeologist, ornithologist, botanists and all the rest of the oligists can find plenty of material to interest them

in a radius of a few miles of Reno.

Many Ancient Relics

The early Indian tribes, their workshops where they manufactured their utensils and war implements; their writings upon the rocks, the race extinct centuries ago.

Then the legends and traditions of the present Indian tribes, Piute and Washoe.

On the early trails of pioneers, evidences of which are still clear of their battles with the Indians; then the battle of Indians and soldiers.

The early animals now passed.

The wonders of Virginia City and the world of matter to be unearthed, that makes impossible fiction tame and uninteresting.

The mines that saved the Union during the time of stress.

The early and present multi-millionaires.

The history of but one of these men that made his immense fortune from the hills, that remained true to his state that gave him his weath, and who is now the premier

factor of the upbuilding of this commonwealth, the one single man that actually lives, has lived, and always will live, within the confines of the borders of Nevada,

a volume in itself.

In every direction are truck gardens, grain fields, hay and fruit orchards; chicken ranches by the score.

The premier racing sire of the year 1922 within the borders of the city on a stock farm of blue bloods that has no equal.

The great basin of the Truckee, wherein Reno is situated, is literally covered with thousands and thousands of white-faced, high-bred cattle, feeding on the stubble

of the thousands of acres of alfalfa.

There are thousands upon thousands of sheep within the confines of this same area.

All over the state of Nevada this same wonderful opportunity, of interest, or upbuilding, is in progress.

Be it known that Nevada is the very last stand of the old west.

What were ghost mining camps of a few years ago are now busy working properties with the wealth of the east, the west, the north and the south

vieing for honest investment.

The new era has arrived.

It is true; it is in the shaping and upon the first rung of the ladder, but under the surface of things can be easily detected the growing, growing

of a commonwealth that in a few years will be second to none in all things.

(THE END)

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen