|

Naval Officers by James Fennimore Cooper 1846 Commodore Melancthon Taylor Woolsey |

|

Naval Officers by James Fennimore Cooper 1846 Commodore Melancthon Taylor Woolsey |

| Background | 1780-1800 | . | . |

| The Adams | 1800 | frigate | 28 guns |

| The Boston | 1803 | frigate | 28 guns |

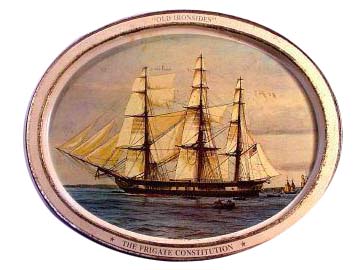

| The Essex and The Constitution | 1803-1807 | frigate frigate | 32 guns 44 guns |

| Building the Lake Boats | 1807-1809 | . | . |

| An Outing to Niagara | 1809 | . | . |

| The Oneida | 1810-1812 | brig | 16 guns |

| The Sylph | 1813 | brig | 4 guns? |

| The Jones | 1814 | brig | 22 guns |

| After the War | 1814-1838 | frigate . | 44 guns |

|

Young Woolsey was born about the year 17822, his parents having married near the termination of the war of the Revolution. His early education was that usually given to young gentlemen intended for the professions, and the commencement of the year 1800 found him a student in the office of the late Mr. Justice Platt, then a lawyer of note, residing at Whitesborough, in Oneida County, and the member of Congress for his district. This was the period when the present navy may be said to have been formed, the armaments of 1798 and 1799 having substantially brought it into existence. Young Woolsey, being of an athletic frame and manly habits, had early expressed a desire to enter the service, a wish that was gratified through the influence of Mr. Platt, as soon as that gentleman attended in his seat in Congress, which then sat in Philadelphia. We ought to have mentioned that Mr. Justice Platt was the husband of a sister of his pupil's mother, and consequently was the latter's uncle by marriage.

Woolsey learned a great deal of the elementary portions of his profession during the few months he served in the Adams. He was of an age to see the necessity for exertion, as well as to comprehend the reasons of what he saw done, and few midshipmen made better use of their time.

In dropping out of the East River into the Hudson, the pilot got the Boston on a reef of rocks that lie near the Battery. Woolsey, who had made himself a good deal of a seaman while in the Adams, was rated as a master's mate on board the Boston, and he was sent ashore with a boat, with orders to go to the navy-agent, in order to direct him to send off a lighter, with spare anchors and cables. On landing, he met the navy-agent on the battery, and communicated his orders. The latter asked Mr. Woolsey to proceed with his boat a short distance, in order to tow a lighter round to a pont where it could receive the ground-tackle needed. Supposing he should be conforming to the wishes of his captain, and knowing that, in consequence of meeting the navy-agent on the Battery, he might still return to the ship sooner than he was expected, the young officer complied. As soon as the duty was over, Woolsey returned on board the Boston, repaired to the cabin, and reported all that he had done. His captain heard him with grave attention. When the midshipman had got through with his story, and expected to be applauded for his judicious decision, the reasons for which he had paraded with some little effort, Capt. McNiell looked intently at him, and uttered, in a slow, distinct manner, the words, "D__d yahoo!" Woolsey remonstrated, with some warmth, but the only atonement he received was a repetition of "D__d yahoo!" uttered in a more quick and snappish manner. This little affair was very near driving our young officer out of the ship; but his good sense got the better of his pride, and he came to the wise decision not to let his public areer be affected by his private feelings. Ships were then difficult to be found; the cruise promised to be both instructing and agreeable, in other respects; and large allowances were always made for Capt. McNiell's humor. We say the wise decision, since an officer is usually wrong who suffers a misunderstanding with a superior to drive him from his vessel. So long as he is right and does his duty, he can always maintain his position with dignity and self-respect.

The Boston was the ship that carried Chancellor Livingston5 and

suite to France, when the former went as a minister to negotiate the treaty for the cessation

of Louisiana. The passage was pleasant enough, until the ship got near her port, when she was

After landing the minister, the Boston, in pursuance of her instructions, proceeded to the Mediterranean, where she was to join the squadron under the orders of Com. Dale. But it did not suit the caprices of Capt. McNiell to come within the control of a superior, and he managed in a way to avoid both of the officers who commanded while the ship was out. He gave convoy, and for a short time was off Tripoli, blackading, but the Constellation appearing before that port, he immediately left it, and did not return. Woolsey used to relate a hundred laughable anecdotes concerning this cruise, during which Capt. McNiell committed some acts that hardly could be excused by the oddity of his character. While the ship was on the African coast, the captain sent for the pilot, a Frenchman, in order to ascertain the position of a particular reef, or a shoal, about which he had some misgivings. Woolsey entered the cabin on duty just as this consultation was held. The Frenchman was pointing to the chart, and he said, a little at a loss to indicate the precise spot, "La-la, Monsieur." "La-la-la, b__r la, where's the reef?" demanded McNiell. On another occasion, while the ship lay at Malaga, Woolsey was sent on shore, at nine, for the captain, who had dined that day with the consul. Sweden was at war with Tripoli, at that time, as well as ourselves, and a Swedish squadron was then at Malaga, the admiral and captains also dining with the consul on this occasion. McNiell was seated between the admiral and one of his captains, when Woolsey was shown into the dining-room. The young man reported the boat. "What do you say?" called out Capt. McNiell. Woolsey repeated what he had said. McNiell now leaned forward, and his face within two feet of that of the admiral, he called out, "These bloody Swedes keep such a chattering, you must speak louder." But these were trifles in the history of this extraordinary man, and we only relate them on account of their connection with the subject of this sketch. After remaining abroad near or quite a twelve-month, the Boston returned home, where her commander was discharged from the service, and the ship was laid up in ordinary, never to be re-commissioned. She was subsequently burned at the taking of Washington. We do not happen to possess the proofs to say whether Woolsey returned to America in the Boston, or whether he joined one of the ships of Com. Morris' squadron, at Gibraltar. We cannot find any evidence that Capt. McNiell ever joined either commodore, and it is not easy to see how one of his midshipmen could have got into another ship without such a junction. At any rate, Woolsey was certainly in the Chesapeake, as one of her midshipmen, while Com. Morris had his pennant flying in her, and he went with that officer to the New York, acting Capt. Chauncey. On the passage between Gilbraltar and Malta, the Enterprise in company, occurred the explosion on board the New York, by means of which that frigate came very near being lost. Woolsey always spoke in the highest terms of the coolness and decision of Chauncey, on this trying occasion, by which alone the vessel was saved. As it was, nineteen officers and men were blown up, or were seriously burned, fourteen of whom lost thier lives. The sentinel in the magazine passage was driven through to the filling-room door, and only a single thickness of plank lay between the fire and the powder of the magazine, when the flames were extinguished.

Woolsey went off Tripoli again, in the New York, and was present when Porter made his spirited

attack on the wheat-boats ashore, and in the abortive attempt that was subsequently made at

cannonading the town. We are not certain whether Mr. Woolsey returned home in the Adams, with

Com. Morris, or whether he continued out on the station until the New York's cruise was up.

There could not have been much difference in the time, however, our young officer serving afloat in

the Adams, Boston, Chesapeake, New York, and, we believe, in the Adams, again, with little or

no interruption, from the time he entered the service, in 1800, to the close of the year 1803.

During these cruises, Woolsey made himself a sailor, and a good one for he was for the time he had

been at sea, and the opportunities he had enjoyed.

In the course of the exchanges that were made, Capt. Campbell took command of the Essex. About this time Woolsey received an acting appointment as a lieutenant, and when Capt. Cambell again exchanged with Com. Rodgers, the latter coming home, and the former remaining out in command, Woolsey went, with a large proportion of the officers of the Essex, to the Constitution 44. In the Constitution, then the commanding ship, Woolsey remained on the Mediterranean station, until near the close of the year 1807. He had, for his messmates, Charles Ludlow, William Burrows, and various other young men of merit. None of the lieutenants, Ludlow excepted, were commissioned, but they were all held in abeyance, with orders to Com. Campbell to report on their qualifications and conduct. That officer was so well satisfied with his young men, however, that in the end each of them got his proper place on the list. In that day lieutenants were frequently very young men, and it sometimes happened that their frolics partook more of the levity of youth than is now apt to occur, in officers of that rank. One little incident, which occured to Woolsey while he was under the command of Com. Campbell, tells so well for the parties concerned, that we cannot refrain from relating it; more especially as the officer whose conduct appeared to the most advantage in the affiar is still living, and it may serve to make his true character known to the country. Com. Campbell had brought with him, to his ship, a near relative, of the name of Read. This young gentleman was one of the midshipmen of the frigate, while Woolsey and Burrows were two of her lieutenants. On a certain occasion, when the latter was "filled with wine," he became pugnacious, and came to voies de fait with his friend Woolsey. The latter, always an excellently tempered man, as well as one of great personal strength, succeeded in getting his riotous messmate down on the ward-room floor, where he dictated the terms of peace. As such an achievement, notwithstanding Burrows' condition, could not be effected without some tumult and noise, the fact that two of the ward-room officers had come to something very like blows, if not actually to that extremity, necessarily became known to their neighbors in the steerage. From the steerage, the intelligence traveled to the captain, and, next morning, both Woolsey and Burrows were placed under arrest. As between the two parties to the scene nothing further passed or was contemplated, they were particularly good friends, and the offender no sooner came to his senses than he expressed his regrets, and no more was thought of the affair. Capt. Campbell himself was willing to overlook it, when he learned the true state of things, and all was forgotten but the manner in which it was supposed the commodore obtained his information. That the last came from some one in the steerage was reasonably certain, and the ward-room officers decided that the informer must have been Mr. Read, on account of his consanguinity to the commanding officer. On a consultation, it was resolved to send Mr. Read to coventry, which was forthwith done. For a long time, Mr. Read was only spoken to by the gentlemen of the ward-room on duty. They even went out of their way to invite the other midshipmen to dine with them, always omitting to include the supposed informer in their hospitalities. Any one can imagine how unpleasant this must have been to the party suffering, who bore it all, however, without complaining. At length Woolsey, while over a glass of wine in the cabin, ascertained from the commodore himself the manner in which the latter had obtained his knowledge of the fracas. It was through his own clerk, who messed in the steerage. The moment an opportunity offered, Woolsey, than whom a nobler or better-hearted man never existed, went up to young Read on the quarter-deck, and, raising his hat, something like the following conversation passed between them. "You must have observed, Mr. Read, that the officers of the ward-room have treated you coldly, for some months past?" "I am sorry to say I have, sir." "It was owing to the opinion that you had informed Com. Campbell of the unpleasant little affair that took place between Mr. Burrows and myself." "I have supposed it to be owing to that opinion, sir." "Well, sir, we have now ascertained that we have done you great injustice, and I have come to apologize to you for my part of this business, and to beg you will forget it. I have it from your uncle, himself, that it was Mr. ___." "I have all along thought the commodore got his information from that source." "Good Heaven! Mr. Read, had you intimated as much, it would have put an end to the unpleasant state of things which has so long existed between yourself and the gentlemen of the ward-room." "That would have been doing the very thing for which you blamed me, Mr. Woolsey -- turning informer." Woolsey frequently mentioned this occurrence, and always in terms of high commendation of the self-denial and self-respect of the midshipman. We had it, much as it is related here, from the former's mouth. It is scarcely necessary to tell those who are acquainted with the navy that the young midshipman was the present Commodore George Campbell Read, now in command of the coast of Africa squadron.

The Constitution was kept out on the station some months longer than had been intended, in consequence of the attack that was made on the Chesapeake, the ship that was fitted out to relieve her. This delay caused the times of the crew to be up, and the frigate was kept waiting at Gilbraltar in hourly expectation of this relief. Instead of receiving the welcome news that the anchors were to be lifted for home, the commodore was compelled to issue orders to return to some port aloft. These orders produced one of the very few mutinies that have occurred in the American marine, the people refusing to man the capstan bars. On this trying occassion, the lieutenants of the ship did their duty manfully. They rushed in to the crowd, brought out the ringleaders by the collar, and, sustained by the marine guard, which behaved well, they soon had the ship under complete subjection. This was done too, as the law then stood, with very questionable authority. Subsequent legislation has since provided for such a dilemma, but it may be well doubted if the majority of the Constitution's crew could have been legally made to do duty on that occasion. So complete, however, was the ascendancy of discipline, that the officers triumphed, and the ship was carried wherever her commander pleased.

Nor was this all. When the Constitution did come home, she went into Boston. Instead of being

paid off in that port, which under the peculiarities of her case certainly ought to have been done, orders

arrived to take her round to New York. When all hands were called to "up anchor," her officers fully expected another revolt!

but, instead of that, the people manned the bars cheerfully, and no resistance was made to the

movement. The men, when spoken to in commendation of their good conduct, admitted that they had been

so effectually put down on the former occasion, that they entertained no further thoughts of resistance.

Woolsey did his full share of duty in these critical circumstances, as, indeed, did all of

her lieutenants. |

|

Background, Adams, Boston, Essex and Constitution, Lakeboats, Niagara, Oneida, Sylph, Jones, After the War |

Home |

Suggested Favorite Pages |

Site Map |

Copyright © 2001, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2001, Mary S. Van Deusen

|