A Campfire Tiger Story - How a Man-Eater Was Conquered

(By An Old Plainsman.)

NIGHTS in the high altitude of Middle park, even in June, are crisp and cool.

Having not yet tried to sleep - an undertaking which I considered not likely to succeed in my own case - I brought driftwood out of the canon with which

to replenish the fire.

The unusual and novel sight must have astonished the wild animals collected in the neighborhood, for a big blaze was soon twisting and curling in the air,

while thousands of sparks darted heavenward, and the camp was lit up with the radiance of noonday.

The light brought our horses into view, where they were picketed or hobbled near by.

"Old Mex," my faithful shepherd, occupied his accustomed place at the feet of my saddle horse.

The latter must have known "Mex" to be an ever vigilant friend, for he would step all round and over the dog without imperiling him in the least.

Our hunting dogs were pretty evenly distributed about camp.

Wherever a saddle blanket rested there a cur was to be found, having worked off their uneasiness and excitement in the presence of the unusual spectacle of

stampeding game.

The bulldog minus some patches of hide and hair, nose toward the fire as if the latter had been created for his individual benefit.

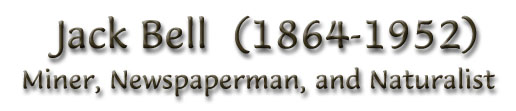

"Jack" Bell, a worthy member of our camping and hunting outfit, owned experience in foreign gamelands, and like Dr. Garvewr, could reel off an interesting camp fire story whenever opportunity afforded.

"Dr. Garver's experience is unique, but not exceptional," he said, when the army surgeon had concluded his story of the man-eating lion.

"Other instances are remembered when the savage animal has shown its contempt for mankind, and its feline tendency to torment without killing the victim outright.

I especially recall an experience of my own in India, in which a man-eating tigress and a native laborer were the principal actors.

"The story may be worth repeating.

The occasion with all its accessories is well remembered by me - everything accompanying and surrounding the adventure comes up before me even tonight as vividly as if it had occurred but yesterday.

The story may appear to bear the impress of fancy, accentuated by time and place, and all the elements that aid in making it dreamlike and unreal, but it is none the less worthy of credence, and, indeed,

the whole adventure was most horribly real, especially to the victim, Chandranahour, the 'abducted' Indian laborer.

"Twilight had gone from the hills, but the full moon was lighting up the forest almost as clear as day - a light, however, that could not be measured or trusted as we can confide in the light of day.

The earth, still hot from the sun, the sudden lull of the breeze, the variegated plaints of nocturnal beasts and insects, the calm, serene beauty of the great arc of heaven above a land still unsubdued by man

after thousands of years of civilization: the ruthless fecundity, savage, vast as the ether, invincible as the ocean, could not but take possession of, amaze, even dominate the human mind.

I felt my heart swell with an indefinable impulse - it was not poetic grandeaur, for I have no poetry in my soul," laughed Bell, "but only the physical elixir of a subtle ozone and the excitement of anticipation.

"Behind me followed a native runner, Bavandjie, and we were preceded by another, Djouna, a guide provided by the village of Nardonares to pilot me to the lair of the tigress, the man-eater, which had that day, in broad daylight,

carried off Chandranahour.

As we advanced into the fastnesses of the wilderness, the murmurs of the night, accentuated no doubt by my prolonged nerve-tension, became louder and more terrifying, the turmoil of beasts of prey and wild animals re-echoed over the plain, and huge bats dashed across the sky.

"The Indian runner, Bavadjie, drew nearer to my side.

His terror was about offset by his pride in being permitted to accompany and serve what the native Nardonares chose to consider a bold and dashing American hunter.

"At the entrance to a broken and rocky defile, the guide, Djouna, halted,, trembling.

He gave a sign with his out-stretched hand, and said in a whisper:

"'The man-eater - she is there!'

"Before us lay a sinuous landscape, one of those secluded corners of the jungle, where the untrammeled forces of nature,

the cross-purposes of the counter instincts of animal and plant life, create a living splendor and a noxious petrefaction.

The moonlight gave a silver filagree to the fig trees, a somber shade to the denser foliage, a ghostly, indistinctness to the overshadowed trunks.

It wove a delicate white lacework over the bendweed, the lichen, the runcina, over a brackish pool that was half choked with the annual growth and death of rushes and water plants.

The sky appeared to be made of scintillating star-mist.

Wild creatures stirred the undergrowth in search of prey, or in flight - the hunted from the hunter.

Everywhere were in evidence the complex throes of birth, death, murder and occult fecundation, sinister shades, the blow of polled flowers,

the heavy vapor of marshland, and the subtle perfumes of aromatic plants.

In the intervals of silence might be heard the sighings of some mysterious, cavernous waterfall, and the distant plaint of jackals.

"'It is an ideal retreat for a man-eater's lair,' I said.

'But do you know the exact position?'

"'One day in winter,' answered Djouna in a low voice, 'while searching the jungle for a strayed heifer, I saw the man-eater at the mouth of a cavern.'

In an almost inaudible whisper, and trembling like one with a chill, he added:

"'She was devouring the remains of a young girl!

Since then Chandranahour, the present victim, witnessed at this same place a like scene!

"'Little doubt, then, that this is the permanent lair of the tigress,' I said.

'So far so good.

But can you lead me to the exact spot?'

"'I can, sahib,' answered the Hindu, and his resignation was that of a doomed man on the march to the gallows.

"We rounded a dense thicket and came to a pathway cut by torrential rains.

The moon, at her zenith, sent an occasional shaft of light through the overhanding foliage to the ground below.

These light-columns made the surrounding darkness seem more dense by contrast.

"We advanced lightly and cautiously, with eyes trying to penetrate the obscurity.

The fret of our clothes against the vines and foliage, the tramp of our feet on the hard pathway could not be distinguished from the other myriad sounds of night.

But a strange, bodeful chill emanated from the undefined denseness of our purlieus.

Peril, like an overshadowing essence, enfolded and gave impress to the scene, changing or turning into cariacature every tree, bush or rock we passed, inscribing

fantastic symbols, grostesque or gruesome, everywhere.

"My two Hindus, at the inevitable approach of danger, fell into a sort of hypnosis, the source of the passive bravery, or rather indifference to personal peril, which has often

been a matter for surprise to the uninitiated occidental.

With dilated pupils, with all feeling and emotion lulled to passivity, they walked like somnambulists, while my own will, nerves and reason were fighting a sharp

battle.

In spite of my keen realization, however, of unpleasant possibilities, I would not allow my purpose to waver.

I had great faith in those days in the strength of my arm, in the cleverness and precision of my sight, and I experienced something

of the electric stamina I imagine a brave man face to face with danger would feel.

"While my mind vaguely considered these things in the non-analytic manner of a man more accustomed to spontaneity of action than measured procedure,

I saw Djouna stop suddenly and turn nervously toward me.

"'It is there, sahib - that open space beyond the ledge of loose rock.'

"We stopped.

I took one of the rifles which heretofore I had allowed Bavadjie to carry in order to assure suppleness and steadiness to my arm at the critical moment.

Silently, with light and careful footsteps, all three of us reached the ledge and knelt behind it.

A subtle ground mist hovered before us and sufficed to render us invisible.

But in looking out over our low bulwark every detail of the open space could be seen, for the ground was encumbered with only a few low plants,

and the full beams of the moon lit up the entire area.

Cautiously I raised myself above the low rock ledge and leaned far over it.

"What I saw filled me with unspeakable horror.

"Toward the middle of the open space, only a few yards away, at the mouth of a den formed by fragments of stone, I saw outlined the form of the colossal tigress.

Between her huge forearm lay Chandranahour.

The man was not dead; he did not seem to be injured even - at least not seriously.

My clear vision in the bright moonlight enabled me to see his eyes open and shut at long intervals, and his breast palpitated with the rapidity of a bird caught in a snare.

The tigress watched him in a seemingly indolent manner, like a cat with a mouse.

And, like the cat, too, she frequently let go her prey; she relapsed into a posture of negligence, or feigned inattention, of somnolent grace.

"I was ready with my rifle, but dared not fire.

A revulsion of fury, of pity, for a moment made my nerves unsteady.

"The awful minutes passed.

Then, slowly, cautiously, Chandranahour moved.

He stretched out his hands and raised himself on his elbows.

The moonlight irradiated his face, distorted by speechless terror.

The contact with death had frozen his tongue and filled his widely distended pupils with stupor.

He turned his face toward the tigress.

She seemed to be looking vaguely elsewhere, sleepily indifferent to the presence of her prey.

Then Chandranahour began to draw himself along and succeeded in gaining several feet distance."

"Ugh! Bell, your story gives me the shivers!" said Gerald Oakley, one of our camp boys, and he seemed to echo the sentiment of the majority of the listeners.

"Give us a lapse until I replenish the fire.

A rousing fire and better cheer are needed to offset the horrors of such realism as you are able to invest a story with.

"It was a very real incident in my life," said Bell, "and in relating it even at this day its horrors are scarcely relieved by time, but recur to my mind

with an intensity beyond the power or possibility of ordinary fiction.

But plain, unvarnished truth always stands out more unique and vivid than the most lavishly colored romance.

"Seeing the livid face of the man nearing me, I brought my weapon to bear on the tigress.

Unfortunately a movement of Chandranahour rendered intervention in his behalf impossible at the moment, for his head came into the line of sight.

I could only condone my luck and wait for a more favorable opportunity.

"Encouraged by the continued indifference of the man-eater, the Hindu began to drag himself along more quickly.

A desperate hope lit up his eyes, but only to die the next moment.

Suddenly she rose and made a bound.

The man, as in a trance, let himself fall to the ground between the great armored paws,

face to face with the glistening teeth and terrifying eyes.

"'She is playing' murmured Djourna, who had cme close to my side.

My soul seemed suddenly darkened.

I saw, looming in hideous apotheosis, the beast which in our own era still in a measure dominates India - ancient India; which is not only the master of man through superior strength

and subtlety, but dares devour him when hunger urges, or, if already surfeited with the blood of inferior beasts, dares to amuse herself

with him as though he were merely unfeeling.

"At that moment there rose in my breast a desperate thirst for vengeance.

The passion overmastered the desire to conquer the man-eater by the administration of a speedy death.

It was a desire to torment her as she was tormenting her helpless victim, to insult her, to make her feel the supremacy of the being that for years she had dared to make her prey.

"I tried to subdue my impulses.

Soon my heart beat more normally.

Anger or shame at the degeneracy of my race no longer clouded my eyes.

I would teach this beast that there was a distinction to be acknowledged and respected between the power and adapability of muscle and the possibilities of reason.

"Meanwhile the tigress, with a purring sound, and with light, nimble movements, turned Chandranahour over and over, seeming to revel in her joy of domination.

The broken spirited man, huddled together, seemed like some infirm herbivore, thin, slight and defenseless against the queen of the jungle.

She, blase, a supple, elegant, awful symbol of the struggle for existence, soon re-commenced her terrible play.

When she was two yards away she remained motionless, and her amber eyes closed slowly.

Hers was the expression of perfect certitude; she already tasted the living repast that she was to enjoy soon.

"The Hindu seemed to have relinquished all hope.

But the instinct to live is always invincible.

It dominates the conviction that all effort is futile.

So, after a moment of uncertainty, Chandranahour raised himself and re-commenced his crawling flight exactly as he had done before.

"This time, thank goodness, I was in full possession of all my faculties.

I allowed Chandranahour's head to pass the line of vision, and made my choice between the prudence of firing straight to the heart and my eager

desire to punish the brute somewhat after her own merciless fashion in dealing with my kind.

The report of my rifle suddenly rang out on the quiet night.

In a cloud of smoke I saw Chandranahour's silhouette raise itself rapidly, and beyond him the stricken tigress with a mutilated paw lifted in an attitude of surprise.

"Courage, Chandranahour@" I shouted to the Hindu, as I leaped over the sheltering ledge of rock with the design of placing myself between him and the tigress.

The Hindu threw himself forward; the tigress made a short, quick bound, but by reason of her crippled paw fell short of her retreating victim.

The beast had not time to repeat the move.

A second shot from my repeater rendered another paw useless.

Overcome, powerless, with redoubled growls and gleaming jaws, the beast lay on the ground more helpless than did her late victim, now only a symbol of force.

Chandranahour, sheltered behind my protecting arm, had, in the revulsion of feeling and excess of joy, lost temporarily the use of his physical faculties.

In a dazed condition he leaned against our breastwork of stone, supported by Djouna.

"I pumped another cartridge into my repeater and took several steps toward the tigress.

She tried to raise herself and crawl toward me, stretching forward her monstrous head, unmasking her powerful teeth and steel-like jaws.

"She fell back powerless, and I, remorseless, contemplated her with a cruel, revengeful satisfaction.

It seemed to me that she now was beginning to comprehend the power of man, that henceforth she would no longer dare

fearlessly to seize her human prey in the village; that at last she would cease to torment, but kill hastily.

"'Sahib,' asked Bavadjie, 'will you not kill the terrible brute?'

"'No, I would rather make her a captive.

I want to teach her the superiority of man.

Is Chandranahour injured?'

"No, only weak and helpless from the horror of his experience.'

'Chandranahour, will you be afraid to remain alone with me while Bavadjie and Djouna go for ropes, canvas, a stretcher and bearers?' I asked.

"'Ah, Sahib! I feel greater safety near you than if I were walled round with barriers of granite.'

"'Then both the Hindus shall go.

Take my rifle - the extra double-barrel, Bavadjie.

My repeater is ample for our defense.

Lose no time and return quickly.'

Having refilled the partially empty magazine of my repeater and pumped a fresh cartridge into the barrel, I saw down upon a moss grown boulder near

the ledge which had been my late defense and contemplated the disabled tigress.

Moments of pity came to me.

But when I turned and looked on the poor Hindu, still exhausted with his awful experience of alternating hope and despair,

involuntarily shaking at every growl of pain from his late tormenter, my anger was fanned afresh until it grew into an inveterate hatred.

"Four hours later the creature was a captive.

Her body was secured by a mesh of strong interlacing cords.

A close framework of bamboo poles formed a sort of impromptu cage."

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen

Copyright © 2012, Mary S. Van Deusen